Main takeaways

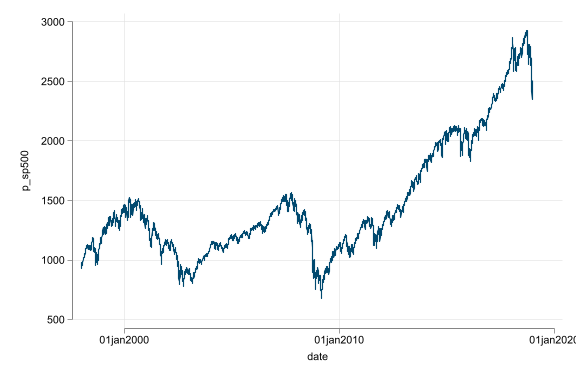

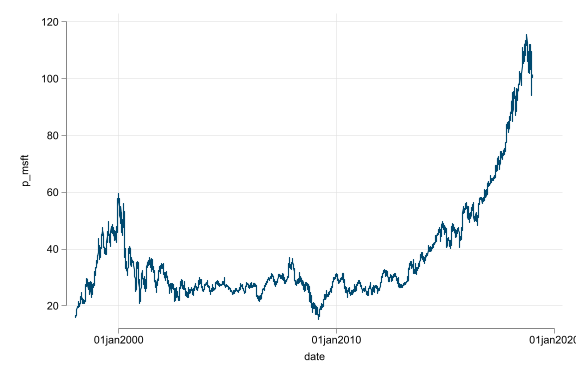

- Regressions with time series data allow for additional opportunities, but they pose additional challenges, too

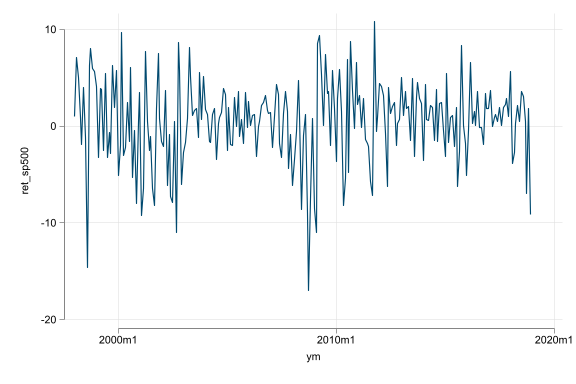

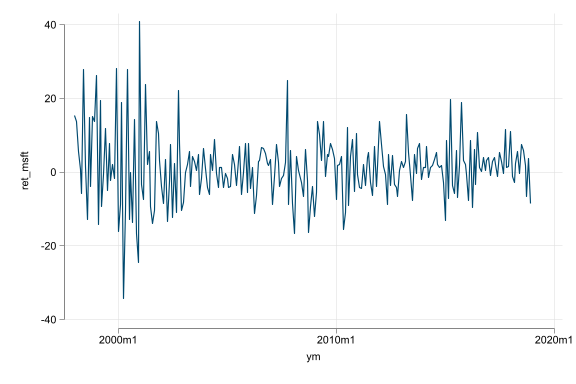

- Regressions with time series data help uncover associations from changes and associations across time

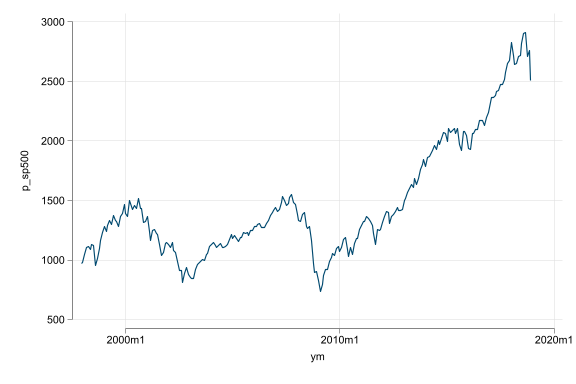

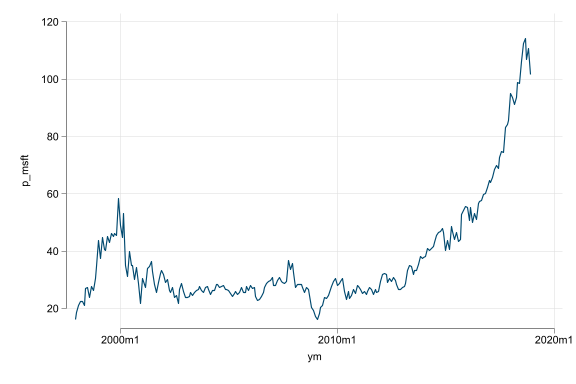

- Trend, seasonality, and random walk-like non-stationarity are additional challenges

- Do not regress variables that have trend or seasonality; without dealing with them they produce spurious results